|

|

![]()

| MAJOR BRUCE ATLEE HUNT |

| 2/13 Australian General Hospital and Medical Officer on the Burma Thailand Railway |

|

Bruce Hunt was born in Sydney on 23 February 1899, the son of Atlee Arthur Hunt, CMG. He was educated at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. On 24 February 1917 he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and served on the Western Front in 1918 as a Non Commissioned Officer (NCO) in the 8th Field Artillery Brigade. |

In July 1930 he set up practice in Perth and was appointed to Royal Perth Hospital in 1932. He was associated with the establishment of a diabetes clinic at the Perth Hospital (later Royal Perth Hospital).

During the Second World War he service in both the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The date of his enlistment in the RAAF is not readily available. However, it is known that he had the Rank of Squadron Leader and that he was discharged from the RAAF on 18 August 1941 and enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) the following day with the rank of Major. His posting on discharge from the RAAF was show as Station Head Quarters, Pearce, in Western Australia. He then enlisted from Perth into the AIF on 19 August 1941. His unit on enlistment was 13 Australian General Hospital (AGH).

The 13 AGH was formed on 11 August 1941. It was originally located at the Caulfield Race Course. Because the 2/10 AGH, which was already in Malaya, was under pressure the 2/13 AGH was instructed to be ready to embark for overseas in three weeks. The unit actually moved from the camp on the Caulfield Race Course to Singapore on 2 September 1941 on HMAHS Wanganella. The ship was immaculate and displayed a large Red Cross on it's hull. The initial establishment of the unit was to be 20 Officers, 51 nurses, 3 masseuses, 21 Warrant Officer and Sergeants, 130 Other ranks - at total of 225. (See detail in the books section of website www.pows-of-japan.net).

In Singapore and Malaya

The voyage to Singapore, via Perth, was completed on Monday 15 September 1941. The unit was initialled established in St Patrick's School at Katong. A significant number of members of the 2/13 AGH were seconded to other medical units 2/10 AGH (at Malacca), 2/9 Field Ambulance and the 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station. On 23 November, the 2/13 AGH took over a medical facility (hospital) at Tampoi from the 2/4 CCS. This old Mental Hospital had been made available to the AIF by the Sultan of Johore, for $25,000. The move to Tampoi was achieved in 2 days.

Japanese invade and Capitulation by Allies

The Japanese invaded Malay and southern Thailand on 8 December 1941. The Japanese forced the Allies down the Malayan peninsular. On 6 January 1942 the 2/10 AGH was redeployed from Malacca to the Singapore Island. 2/13 AGH took over the main responsibility for the AIF on the Malayan mainland. Later the 2/13 AGH was moved onto the island and returned to St Patrick's School at Katong (the Colonial Secretary had refused the Unit use of other facilities). The Hospital was kept busy treating sick and wounded. Surgeons and staff were often operating around the clock. Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. It is well known that the Nursing Sisters of the Medical Units were evacuated from Singapore in the days shortly before capitulation.

As Prisoners of War

After capitulation, an Allied General Hospital was established at Roberts Barracks on 10 March 1942 with 2,500 patients. It was during this period that Private FW (Bill) Fitch a medical Orderly in the 2/3 Motor Ambulance Convoy (MAC) worked with and under Major Hunt in the Roberts Barracks. Bill recalled that over the period of around 12 months that he worked with Hunt and that they were firstly in the Medical Ward and later in the Dysentery Ward. It was during this period in the Dysentery ward that a patient was showing little improvement. Bill Fitch had taken the trouble to read up a Medical Book and thought he knew what was wrong with the patient. Bill then told a Senior MO in the ward that he thought he knew what the patient's problem was. He was informed to leave the diagnosis to the doctors. When Hunt heard of this, he was annoyed and went out of his way to congratulate Bill and inform him that his diagnosis had been correct. (Later when Bill Fitch was on the Burma Thailand Railway as a part of "K" Force (caring for the native labourers (Romusha)), on more than one occasion, he was without a doctor. Then he was pleased he had been well trained by Major Robert Dick and Captain Des Brennan, who were the Medical Officers in the 2/3 MAC. Bill also had taken the time to broaden his medical knowledge, whenever the opportunity arose). Also in the period 1942-43 that the bulk of the POWs remained in Singapore, Hunt was involved with other Medical Officers in making up detailed statements of the basic requirements of a diet. Later Hunt was the AIF representative on a nutritional advisory committee and he did an investigation of the value of certain treatments of dysentery.

In April 1943, the Japanese sent 7,000 POWs (3,400 British and 3,600 Australians) to Thailand (then known as Siam) as a draft known as "F" Force. Each nation had it's own Medical Officers. The Australian MOs were Majors RH Stevens (SMO), BA Hunt, EA Rogers, Captains RL Cahill, FJ Cahill, PIA Hendry, JL Taylor MC, RM Mills, V Brand MC,and CP Juttner. (articles about each of these MOs can be read on www.pows-of-japan.net). Major Stevens was the Senior Medical Officer (SMO) but for various reasons Hunt inherited the role of SMO.

The POWs were moved to Thailand in train loads of around 600 men over a period of around 13 days. The Australians moved first. Major Bruce Hunt was on the 4th train. On arrival in Thailand at a location called Banpong, they were quartered for a night in filthy huts. But, then they started the march of nearly 300 kilometres, which was to last about 18 days. The march was done at night to avoid the intense daytime heat of 45 degree Celsius, but nothing could avoid the muddy tracks they trudged along. The details of the train journey from Singapore to Siam and the march Banpong (Siam) to the Burma border) is covered in some detail in some books and articles and I do not propose to go over that again..

Major Hunt and other medical personnel usually marched at the rear, to gather up the lame etc. When they got to a major camp at Tarsoa it was discovered that there were 37 men unfit (27 with infected feet and 10 with malaria) to march on. A Japanese Medical Officer (MO) was approached and he agreed that none of these men was fit to march on. However, the Japanese MO was not responsible for the party on the march. A Japanese Corporal (thought to have actually been a Korean named Toyama) was in charge. He said that only 10 could remain. Negotiations failed and subsequently, Hunt and a Major Cyril Wild stood in front of the 37 men. The Japanese Corporal beat both Hunt and Wild with a bamboo. Wild had the bamboo thrust into the area of his genitalia and Hunt was also beaten. A bone in Hunt's left hand was broken. Eventually just 10 were allowed to stay behind. Of those who were forced to march on was Chaplain AR Dean VX39407 (DOB 27 Dec 1903). He was an older man and unfit to undertake such a march. He was left in a staging area a little further north and soon after died.

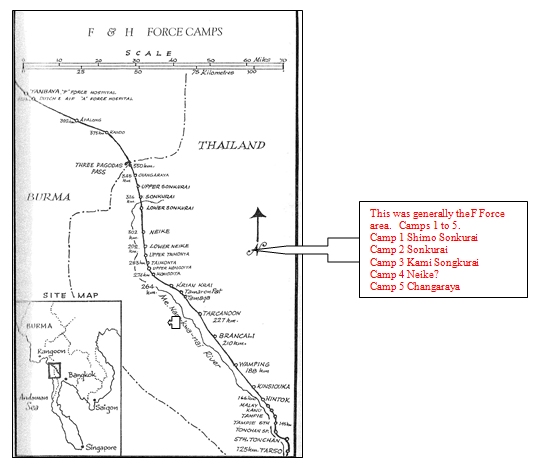

At the end of the march "F" Force was distributed in the vicinity of the border with Burma basically over a distance of 40 kilometres as shown below.

- persuaded the Japanese Commander Colonel Banno to allow the POWs to clean up the filthy area which had been allocated as their POW Camp, before starting work as slaves on the Railway.

- introduced the "Wardmaster" system in the hospital huts, where combat officers became Wardmasters and were responsible for e.g. rolls, cleanliness of the hut, meals etc. This enabled the Medical Orderlies (one should not underestimate their role in caring for the patients) to concentrate on caring for the patients.

- liaised with adjacent "F" Force camps. The British Camps (he was not always welcomed - possibly associated with the mother country / colony syndrome).

- obtained medicines for the patients by deception

- badgered those refusing food to eat.

Wardmastering There were a number of Combat officers who acted as Wardmasters. They included Captain George Gwynne (2/4 Machine Gun Battalion), Lieutenants Norm Dean (2/26 Battalion), Bernie Berry (2/10 Field Regiment), Ian Perry (2/1 Heavy Battery (Captured on Timor)) amongst others.

In 2006 Bernie Berry (since deceased) provided me with the following material about Bruce Hunt, who he worked closely with as a Wardmaster.

WARDMASTERS - 12/12/2006

This was the title given to a small number of officers, who, without exception, had no medical training. Their duties were to supervise the administration and running of their allotted wards, and ease, wherever possible, the work-load on an already over-stressed medical team.

This included keeping records, to be supplied to hospital H.Q.; drawing food from the camp cook-house; water from the source of supply; maintain wood supply for night illumination; keeping the ward as clean as possible, under very adverse conditions; removal of dead to the cremation area; accompany the doctor on his rounds; plus many other unexpected tasks.

The manpower required to attend to the varied demands of running the ward was supplied from the less-stricken patients. This had it's problems in my ward, as all patients were suffering from dysentery or tropical ulcers, and both in many cases.

To the everlasting credit of all concerned, for most of the time sufficient numbers of volunteers were on hand to cope with the task. The Australians were outstanding, but in fairness to my English patients, the Australians had a much higher recovery rate - and a much lower death rate.

At Tanbaya, the medical personnel allotted to my ward of 170 dysentery and tropical ulcer sufferers, was an Indian army medico WOII Pat Wolfe, who on account of other commitments, could only manage spasmodic visits to my ward. He was a very conscientious and apparently capable man, and the lack of any medical equipment or supplies caused him a great deal of worry.

In addition to Pat Wolfe, a small number of A.A.M.C. orderlies were also on strength, but under the overall conditions in the ward, medical training was not a great advantage. All that could be done was to try and make desperately sick and suffering young men as comfortable as possible. Sadly, so much of their dedication was in vain.

The so-called "wards" were very basic structures built from local materials. Their original purpose was to house the POWs and conscripted labour who were to build the railway.

The buildings were primitive in every aspect - earth floors, no form of lighting or water supply. The design was obviously the most economical method of housing a very expendable work force. The sleeping quarters took the form of a raised platform, approx. one metre high, running the full length of the un-partitioned building and floored with bamboo slats.

By the time the buildings were occupied by "F" Force at both Shimo Songkurai and Tanbaya, they were badly in need of extensive repairs especially the atap roofs.

Of all the never ending list of shortages in the ward, the complete absence of bedpans caused a constant battle to maintain even basic hygiene, especially in a dysentery ward.

At the ripe old age of ninety-one the most firmly imprinted memories of the 3-½ years I spent in captivity, the eight months on the railway are the most significant.

I saw many sights that are best forgotten, but, as with other experiences, there is often a good message to counteract the bad.

I have never ceased to remember the courage displayed by so many young men, under terrible conditions, who volunteered to tend their comrades, who in many cases were inflicted with highly contagious complaints.

Sadly, their acts of compassion sometimes cost them their own lives.

(Sgd.) B.K. Berry formerly Captain QX4397 2/10 Field Regiment 11 December 2006

Further detail about the Wardmaster Scheme by Captain George Gwynne (2/4 Machine Gun Battalion) follows. George Gwynne was a solicitor in Perth pre and post war and his report mirrors his legal training:-

Re: The Wardmaster System

The Wardmaster system came into operation in Thailand and Burma through forces of circumstances. The conditions which prompted its inception were unusual and difficult in the extreme. It will therefore be necessary to deal with these conditions in considerable detail in order to demonstrate fully the difficulties of hospital control which resulted in the inauguration of this system.

I am writing this as a combatant officer with no previous knowledge of hospitals or medical services; however, I have seen such services operating at Shimo Sonkurai, No. 5 Camp, Kendo, Tanbaya (Burma) and Kanchanaburi. At Shimo Sonkurai my experience was that of a patient, at No. 5 Camp and Kendo as O.C. of a party of sick personnel en route to Tanbaya, and at Tanbaya and Kanchanaburi as a Wardmaster. I am thus writing on a subject of which I have first hand experience.

Generally speaking descriptions of conditions appertaining will apply to both Thailand and Burma, whereas particular instances will have occurred at Tanbaya which was a hospital only. All other hospitals with the exception of that at Kanchanaburi were working camp hospitals.

'Hospitals'. To the average person the word "Hospital' conjures up the picture of a substantial building, adequately illuminated with iron bedsteads and white sheets staffed by sisters in spotless uniforms and clean cheerful orderlies anxious to satisfy the requests and to attend to the comfort of their patients. The word also presupposes reasonably pleasant surroundings.

Imagine instead Thailand in the wet weather. If one has no experience of a wet season in the tropics let him picture himself living for weeks on end in a bath tub and shower running full strength and instead of a granolithic floor a mud one. If this impression one be registered it is easy to realise the initial major problems with which hospitals administrations were confronted - roofing and drainage.

When the troops arrived at their respective destination having marched under appalling conditions distances varying from 180 to 300 miles without adequate footwear, rest or food, they were met with the sight of numbers of skeleton huts.

These huts were constructed of bamboo in their entirety with a passage way approximately 6 feet wide down the centre and contained 30 bays 10 feet in width and 12 feet in depth on each side of the passage. Outside entrances appeared at intervals of ten bays each, thus subdividing the large hut into three blocks of 20 bays each. The huts were constructed in the main on the sides of hills consequently the bays were high on one side necessitating the use of ladders for ingress and aggress while the other side was correspondingly low. The stagings were made of split bamboo. Mats were provided but not in sufficient quantity to make more than 30% of the troops to any degree comfortable.

The passage ways were obstructed at irregular intervals by roots of bamboo outcrops, roots and stumps of large trees which had been hastily felled during construction and water courses running through. At night it was only possible with the greatest difficulty to move from one end to the other. To add intention of the I.J.A. to cover the roofs with attap but this did not become available form some weeks and then was laid by our own troops. Some tents and tent flys were provided after a few days but in the majority of cases they were perished and the protection they afforded was an inverse ratio to their nuisance value.

At Tanbaya the huts were constructed on a slightly different pattern. Each hut contained one length of 25 bays of similar dimensions with a passage on one side only. On the opposite side of the passage was an attap wall with doorways every four bays. The huts were roofed with attap which was in the majority of the huts the roofing afforded practically no protection. The flooring of the bays was also in very bad condition large gaps appeared in nearly every bay rendering it almost impossible for patients to make themselves comfortable. Some mats and some bags were provided but again insufficient to go around. It was in these circumstances that hospital was established.

The first troops arrived at Shimo Sonkurai on 15th May and on that day the hospital opened at the extreme northern end of the camp and at first occupied a portion of one hut only. On 30th May the hospital admissions had increased to 400 and on the following day they increased to 800 when all ambulant dysentery patients were admitted.

Cholera broke out on 17th May necessitating the construction of an isolation hospital just north of a stream which bounded the camp.

Almost from the commencement there were insufficient AAMC orderlies to cope with the increasing numbers of patients. Volunteers were called for with immediate response from members of combatant units. Consequently, at Shimo Sonkurai nursing was performed by AAMC orderlies and Volunteers working side by side.

At Shimo Sonkurai there were 4 Medical Officers who were working practically 21 hours a day on medical duties alone, and had very little time to give the ward administration. As a result of this Major B.A. Hunt the Camp SMO obtained the services of combatant Officers to manage wards thus inaugurating the Wardmaster system which has so successfully operated there at Kami Sonkurai at Tanbaya and at Kanchanaburi.

Wardmasters. It was quite clear to me from the commencement of my association with hospitals that the secret of successful management was careful and intelligent organization. How essential this was at Shimo Sonkurai can by judged by the fact that containers for the issue of food were as scarce that only two wards could be fed at a time. This is just an instance to show how rigorously a timed programme for meals had to be followed. In the wards the Wardmaster was in the position of a Company Commander own Nursing sister. He has to watch carefully and organise unerringly his domestic duties paying particular attention to sterilization of mess area provision of boiling water for drinking and cleanliness of quarters. Strange as it may seem it took weeks to educate troops to sterilize their mess gear, as a precaution against cholera, and to drink boiled water only. With the aid of a Ward CSM and clerk - both ward inmates - the maintenance of fires, the obtaining of wood and the carrying, boiling and issuing of water was organized. At the time of writing this I almost wonder why such ordinary and apparently simple things should be mentioned but at the time they presented very real difficulties owing to the shortage of man power. The Wardmaster who failed at any time to have such services running smoothly soon saw the failure reflected in the mental and physical condition of his patients.

Messing. With a ward largely consisting of bed patients messing presented a difficulty which required careful attention. Firstly all mess gear had to be collected, sterilized and returned to the rightful owners. This necessitated in itself a considerable quantity of boiling water which was kept at the boil during the process of sterilization. Mess was then served with the maximum of speed under the supervision of an NCO preferably an experienced man. Speed was essential so that containers could be returned for other wards. When the meal was concluded any swill was collected mess gear washed up and returned to patients. With a ward of 130 finishing a meal to everyone's satisfaction was a big job. It was probably the most essential of many in a Wardmasters day because so much depended on the complete consumption of all available food. To live, patients had to eat but if left to themselves a very large proportion would not look at food much less eat it. They complained that food nauseated them they could not eat rice anyway and all sort of other excuses many of them quite understandable in view of their physical condition but they had to be compelled to eat. The Wardmaster soon got to know the finicky eaters and then spent each meal time in persuading cajoling begging or bullying those particular patients. On occasions I have had to resort to forced feeding and have had to hold men's noses to make them open their mouths. It was often necessary to make Nursing Orderlies feed people who refused to do so themselves but eat they must and eat they did. I believe that a considerable number of men on this force died of starvation alone. You will probably say the Wardmaster system saved many lives in this way alone. You will probably say "What about Nursing Staff was this way their job"? I will deal with that aspect later when discussing staffs. It was very noticeable at Tanbaya that the most difficult patients to feed came from camps such as Sonkurai No. 5 Camp Niecke, where Wardmasters were not operating. A great many of these troops were lamentably debilitated through self starvation and resented forced to eat. To my mind the strongest argument in favour of the system was a comparison of the physical condition of patients from Shimo Sonkurai with those from other camps.

Certain patients were in receipt of special diets and it was always necessary to check on the special orderly to see that the patient received his extra food. It was not uncommon for a patient to say he did not feel like food and to endeavour to give away the very food which would probably save his life.

Treatment. Although the Wardmaster had no medical training he was vested with absolute authority in his ward and everyone in that ward was responsible to him, including the Medical NCO in charge of nursing staff. In the average ward treatments were many and varying. Admittedly patients with similar diseases were inmates of the same ward but even so their treatment differed. It was primarily the duty of the medical NCO to keep his treatment records up to date each day after the MO's round and to administer in due course any treatment required. The Wardmaster had continually to satisfy himself that the correct treatment as laid down was being carried out. It was surprising the number of times that patients were overlooked or neglected particularly in busy wards. They would have not received adequate treatment in the absence of the Wardmaster.

Hygiene. Absolute cleanliness of wards was one of the few safeguards against the spread of disease - particularly dysentery which could have resulted very easily in a more appalling death rate than actually happened. The greatest difficulty was experienced at Tanbaya in the initial stages in training patients in ordinary domestic cleanliness and in preventing them from defecating and urinating just wherever and whenever they felt inclined. Bed patients were often too lazy to call for a bedpan or at any rate to call early enough and would defecate through the slats of the bay. Others - sometimes light duty personnel - would again through laziness - defecate in the passage way or through the slats without any thought of their health or that of anyone else. At Tambaya this filthy and dangerous practice was so bad at first that picquets with bamboo canes were mounted on latrines and within wards during the hours of darkness in an endeavour to compel troops to use the latrines and not the adjacent surroundings. The most extraordinary aspect of this serious state of affairs was the disinclination or the point blank refusal of other patients to name the culprits who must have been known to some of them.

Some of the language used by me in explaining to the Ward what I thought of these people and what would happen to them if they were apprehended was neither printable nor creditable, nor did it have much effect. However I caught a light duty man in the act of urinating between the slats one morning and promptly knocked him down. The condition of the ward improved overnight and eventually the average patient became hygiene minded. The lack of the Wardmaster's influence was clearly reflected in the personnel from camps other than Shimo Sonkurai. Indiscriminate defecation and urination as well as general lack of ward discipline were characteristic of their behaviour.

Personal cleanliness also came within the purview of the Wardmaster. The Medical staff attended to the washing of the bed patients, but walking patients had in many instances to be driven to wash themselves and their clothing.

Morale. Apart from looking after and attending to the physical requirements of the patients, the Wardmaster's primary object was the maintenance of morale. The most effective way of doing this was by personally visiting every man at least once a day, listening to his troubles and discussing with him any subject as far removed as possible from his complaint; also keeping him advised of any camp gossip. Food and the iniquities of the kitchen staff were a constant source of conversation. The patience of Job was required. The same stories were told day after day and the same answers given. Another visit was advisable after dark because I consider a cheerful word that time of day when things always appear worse, very helpful.

Entertainment at night was also the Wardmaster's responsibility - lectures and talks generally - and was found to be of the greatest help in the bolstering up of morale. It must be remembered that there was no illumination of any kind - except of course fires - and the hours between 2100 and 2230 were pretty miserable without something to distract the patient's thoughts from his ailments.

Canteens came under this healing. At Shimo Sonkurai and Tambaya canteen supplies were neither regular nor adequate but were of tremendous importance to troops when they did arrive. Tobacco was in particular request, and the immediate distribution made a great difference. If for instance tobacco was held overnight when it could have been issued late in the evening, the spirits of the average ward showed a marked decline.

Staff. The handling of a ward staff, particularly in a very sick ward was the most difficult task a Wardmaster had to perform. As previously stated, for the system to work properly he must have absolute control over the medical NCO who is nominally in charge of the nursing side of the ward under the supervision of the ward medical officer. Otherwise if his common sense suggests to him that patients are not being properly handled he is powerless to act.

At Tanbaya the medical personnel were drawn from NCO's and none of the RAMC and AAMC who had previously worked at various camps from No. 5 Camp to Neike, excluding Kami Sonkurai from which no personnel sick or otherwise were sent to Tanbaya. I do not know how or by whom these medical personnel were detailed for Burma, but I do know from personal experience that they were not truly representative of their units. Many were singularly lacking in those attributes which are normally associated with Army Medical Units.

As regards RAMC personnel generally I found a lack of adaptability which I can only attribute to their training. They were slow to improvise where improvisation meant existence. There were a number of particularly able and conscientious dressers among them but a greater proportion were lazy. If a member of the RAMC was good he was excellent - if not he was useless in a technical sense.

The AAMC personnel were more at home in the difficult and uncomfortable conditions in which they were compelled to work but they were often unreliable and on occasions their attitude to patients left a lot to be desired.

There were however some outstanding NCO's from both Corps. Chronic illness was of course rife amongst medical personnel. One small medical unit lost 29 NCO's and men by illness.

The volunteer orderlies often NCO's, were by and large a long way ahead of the personnel of the medical units. They were enthusiastic in the extreme and individually took a personal interest in their patients. They never hesitated to perform the most unpleasant and dirty jobs, and very soon acquired the art of dressing. Procrastinatic so evident in medical personnel, was not one of their faults.

Deaths. The death rate during the cholera epidemic and later at Tanbaya was naturally high and every individual death required the immediate attention of the Wardmaster to take possession of any kit. It was not possible to trust anyone - again with the exception of a few NCO's - to take charge of a dead man's kit which if not immediately taken over by the Wardmaster rarely contained anything of value. At night it was not possible to do this but often men died during the night without being discovered till dawn. Consequently the Wardmaster first duty at reveille was to collect what was left of the gear of men then discovered. The neighbours of the dead were often less trustworthy than the orderlies. If a sick man was in possession of a watch, the Wardmaster usually endeavoured to obtain possession of this by some subterfuge or other. Rarely was a watch discovered in the possession of a dead man.

Paper. The duties of a Wardmaster were not any easier by the complete lack of paper. He became accustomed to writing on bamboo in Thailand but in Burma suitable bamboo was unavailable and it was necessary to use long narrow strips. Accurate rolling keeping was consequently a work of art. One's patience was tried to its limits when a sudden deluge of rain swamped the administration bay making all bamboo records unreadable.

General System. Once a day all the Wardmasters attended a conference called by the SMO at which any subject affecting the general running of the hospital was discussed.. This resulted in a Wardmaster being kept right up to date in all hospital affairs, likewise the administration was fully aware of what was going on in the wards.

Conclusions. The system is an excellent one anywhere and is absolutely essential in hospitals where MO's, owing to pressure of work, cannot possibly control the internal organisation of wards. Understand the normal establishment for a 600 bed hospital provided for at least 15 MO's.

A wardmaster is on duty 24 hours a day. He must be even-tempered but willing and able to hit hard if necessary.

I am satisfied that no one can eulogise sufficiently the work of the Medical Officers who staffed the Hospitals at Shimo Sonkurai, Tanbaya and Kanchanburi, particularly the two former where conditions were at their worst. Never have I seen such untiring efforts made to save life and relieve pain at all hours of the day and night.

Only first class organisation and daily attention to detail prevented Tanbaya from becoming a place of death and misery.

(Sgd.) George W. Gwynne Captain 2/4 M.G. Bn. A.I.F.

Lt Ian Perry wrote an account of his experiences as a POW. Around 2005, his daughter Vicki provided me with a copy of his papers, which included copies of letters written immediately after the War but before being repatriated to Australia.

The full text of Ian Perry's papers are published in the Books section of my website www.pows-of-japan.net It is worth noting a few lines from a letter he wrote from Changi, Singapore on 10 September 1945. "I have a letter from one of the senior officers who was with me (or who I was with) and really one of the most outstanding men I have ever met ( Bruce Hunt - he is a Major AAMC and …………….) that I'll be proud to keep."

The sickness and death rate of the total "F" Force rose. It is well known that around 2,000 British and 1,000 Australians died from "F" Force. Major Hunt prevailed on Colonel Banno to allow the large number of sick to be moved to an area where conditions would be better. When approved by the Japanese, perversely, the move was not back down the rail trace, but, forward into Burma to a location called Tanbaya. The area at Shimo Songkurai

Article compiled by Lt Col (Ret'd) Peter Winstanley OAM RFD JP. The significant assistance of Dr Don Gutteridge (who will publish a book about Bruce Hunt in the near future) is acknowledged. Reference was made to the following-

- "Medicos and Memories", book co-authored by Drs Jim Dixon and Bob Goodwin (both of whom were POWs of the Japanese) and who approved using their material.

- Royal Perth Hospital Historical Archives.

- An article authored by Professor Geoffrey Bolton and Professor Alex Cohen.

- Copy of an Obituary about Bruce Hunt, given to me by Captain (Dr) Lloyd Cahill, who was a fellow POW Medical Officer, who was closely associated with Hunt during their time on the Burma Thailand Railway.

- Comments provided to me by Bill Fitch who was a Medical Orderly in the 2/3 Motor Ambulance Convoy (2/3 MAC) and who worked with Hunt in the Allied General Hospital (Roberts Barracks) in 1942 and early 43.

- Comments provided to me by Captain (Dr) Peter Hendry who was also a fellow Medical Officer in proximity to Hunt on the Burma Thailand Railway.

- "The Story of 13 AGH" as compiled by Lex Arthurson and provided to me by Lex.

- "Heroes of F Force" collated by Don Wall ISBN 0 646 16047 8 (copies are still available)

- An article published in the West Australian Newspaper on 29 November 1945 titled "Under the Heel - The Siam Burma Railway - How Australian P.O.W. Suffered". This was written by Bruce Hunt and must have been one of the earliest accounts of conditions under the Japanese. This information was in the public arena, before the books written by Rohan Rivett (Behind Bamboo) and Russell Braddon (Naked Island) which were published 1946 and 1952 respectively).

- "Medical Middle East and Far East" by Allan S Walker - published 1953.

- "We Came Home" or "Return from the Land of Milk and Honey" by Richard Armstrong ISBN 0 85905 352 0

|

|